Artificial intelligence (AI) is the hottest buzzword at the moment, and almost every major company is adding some kind of AI features to its product or service. Unfortunately, while the term sounds like it should have an easy and clear definition, it really doesn’t. What researchers call a minor advance in machine learning (we’ll get to that term), some marketing department is billing as a huge step toward artificial general intelligence (we’ll get to that one, too).

In a Financial Times profile, sci-fi writer Ted Chiang described artificial intelligence as “a poor choice of words in 1954.” And, as someone who’s been writing about developments in AI for the last decade, I feel there’s a lot of truth to that. The terms and definitions involved are so nebulous that it’s hard to have a genuine discussion about AI without first outlining exactly what you mean by it.

So let’s explore what artificial intelligence is, why it’s so hard to define well, how we got to this point, and what it can do. I’ll do my best to lay out everything I’ve learned over the last few years as simply as possible so that you, too, can be just as frustrated by how hard everything is to summarize.

What is AI?

Artificial intelligence is a machine that’s able to learn, make decisions, and take action—even when it encounters a situation it has never come across before.

As with what constitutes intelligence in humans, AI is hard to neatly draw a box around.

In the broadest possible sense, artificial intelligence is a machine that’s able to learn, make decisions, and take action—even when it encounters a situation it has never come across before.

In the narrowest possible sci-fi sense, many people intuitively feel that AI refers to robots and computers with human or super-human levels of intelligence and enough personality to act as a character and not just a plot device. In Star Trek, Data is an AI, but the computer is just a supercharged version of Microsoft Clippy. No modern AI comes close to this definition.

In simple terms, a non-AI computer program is programmed to repeat the same task in the same way every single time. Imagine a robot that’s designed to make paper clips by bending a small strip of wire. It takes the few inches of wire and makes the exact same three bends every single time. As long as it keeps being given wire, it will keep bending it into paper clips. Give it a piece of dry spaghetti, however, and it will just snap it. It has no capacity to do anything except bend a strip of wire. It could be reprogrammed, but it can’t adapt to a new situation by itself.

AIs, on the other hand, are able to learn and solve more complex and dynamic problems—including ones they haven’t faced before. In the race to build a driverless car, no company is trying to teach a computer how to navigate every intersection on every road in the United States. Instead, they’re attempting to create computer programs that are able to use a variety of different sensors to assess what’s going on around them and react correctly to real-world situations, regardless of if they’ve ever encountered it before. We’re still a long way from a truly driverless car, but it’s clear that they can’t be created in the same way as regular computer programs. It’s just impossible for the programmers to account for every individual case, so you need to build computer systems that are able to adapt.

Of course, you can question if a driverless car would be truly intelligent. The answer is likely a big maybe, but it’s certainly more intelligent than a robotic vacuum cleaner for most definitions of intelligence. The real win in AI would be to build an artificial general intelligence (AGI) or strong AI: basically, an AI with human-like intelligence, capable of learning new tasks, conversing and understanding instructions in various forms, and fulfilling all our sci-fi dreams. Again, this is something that’s a long way off.

What we have now is sometimes called weak AI, narrow AI, or artificial narrow intelligence (ANI): AIs that are trained to perform specific tasks but aren’t able to do everything. This still enables some pretty impressive uses. Apple’s Siri and Amazon’s Alexa are both fairly simple ANIs, but they can still respond to a wide number of requests.

With AI so popular right now, we’re likely to see the term thrown around a lot for things where it doesn’t really apply. So take it with a grain of salt when you see a brand marketing itself with the concept—do some digging to be sure it’s really AI, not just a set of rules. Which brings me to the next point.

How does AI work?

Currently, most AIs rely on a process called machine learning to develop the complex algorithms that constitute their ability to act intelligently. There are other areas of AI research—like robotics, computer vision, and natural language processing—that also play a major role in many practical implementations of AI, but the underlying training and development still start with machine learning.

With machine learning, a computer program is provided with a large training data set—the bigger, the better. Say you want to train a computer to recognize different animals. Your data set could be thousands of photographs of animals paired with a text label describing them. By getting the computer program to crunch through the whole training data set, it could create an algorithm—a series of rules, really—for identifying the different creatures. Instead of a human having to program a list of criteria, the computer program would create its own.

This means that businesses will have the most success adopting AI if they have existing data—like customer queries—to train it with.

Although the specifics get a lot more complicated, structured training using machine learning is at the core of how both GPT-3 and GPT-4 (Generative Pre-trained Transformer 3/4) and Stable Diffusion were developed. GPT-3—the GPT in ChatGPT—was trained on almost 500 billion “tokens” (roughly four characters of text) from books, news articles, and websites around the internet. Stable Diffusion, on the other hand, used the LAOIN-5B dataset, a dataset with 5.85 billion text-image pairs.

From these training datasets, both the GPT models and Stable Diffusion developed neural networks—complex, many-layered, weighted algorithms modeled after the human brain—that allow them to predict and generate new content based on what they learned from their training data. When you ask ChatGPT a question, it answers by using its neural network to predict what token should come next. When you give Stable Diffusion a prompt, it uses its neural network to modify a set of random noise into an image that matches the text.

Both these neural networks are technically “deep learning algorithms.” Although the words are often used interchangeably, a neural network can theoretically be quite simple, while modern AIs rely on deep neural networks that often take into account millions or billions of parameters. This makes their operations murky to end users because the specifics of what they’re doing can’t easily be deconstructed. These AIs are often black boxes that take an input and return an output—which can cause problems when it comes to biased or otherwise objectionable content.

There are other ways that AIs can be trained as well. AlphaZero taught itself to play chess by playing millions of games against itself. All it knew at the start was the basic rules of the game and the win condition. As it tried different strategies, it learned what worked and what didn’t—and even came up with some humans hadn’t considered before.

AI fundamentals: terms and definitions

Currently, AI can perform a wide variety of impressive technical tasks, often by combining different functions. Here are some of the major things it can do.

Machine learning

Machine learning is when computers (machines) pull out information from data they’re trained on and then begin to develop new information (learn) based on it. The computer is given a massive dataset, trained on it in various ways by humans, and then learns to adapt based on that training.

Deep learning

Deep learning is part of machine learning—a “deep” part, in that the computers can do even more autonomously, with less help from humans. The massive dataset that the computer is trained on is used to form a deep learning neural network: a complex, many-layered, weighted algorithm modeled after the human brain. That means deep learning algorithms can process information (and more types of data) in an incredibly advanced, human-like way.

Generative AI

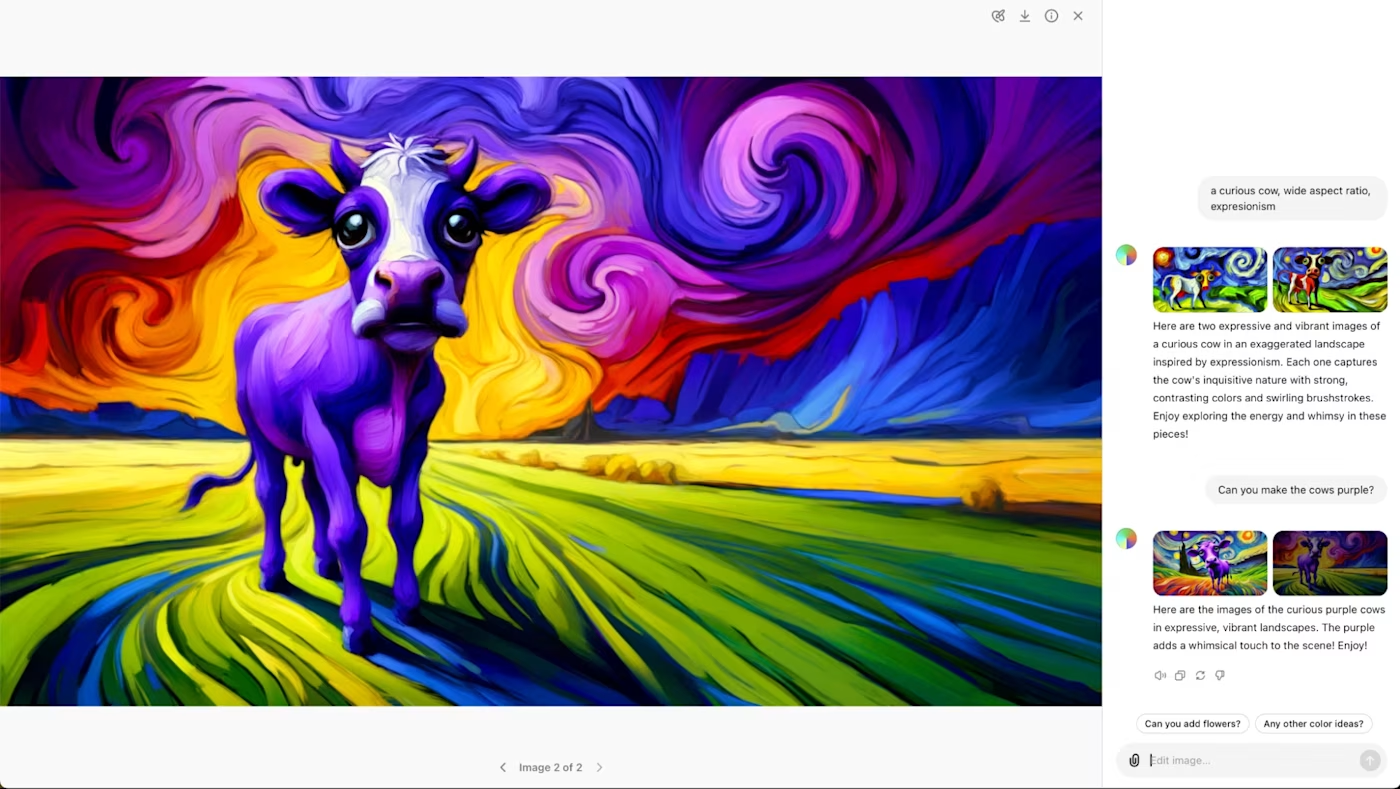

Generative AIs like GPT and DALL·E 2 are able to generate new content from your inputs based on their training data.

GPT-3 and GPT-4, for example, were trained on an unbelievable quantity of written work. It basically amounts to the whole of the public internet, plus hundreds of thousands of books, articles, and other documents. This is why they’re able to understand your written prompts and talk at length about Shakespeare, the Oxford comma, and which emojis are inappropriate for work Slack. They’ve read all about them in their training data.

Similarly, image generators were trained on huge datasets of text-image pairs. That’s why they understand that dogs and cats are different, though they still struggle with more abstract concepts like numbers and color.

Here are a couple more articles to peruse about generative AI:

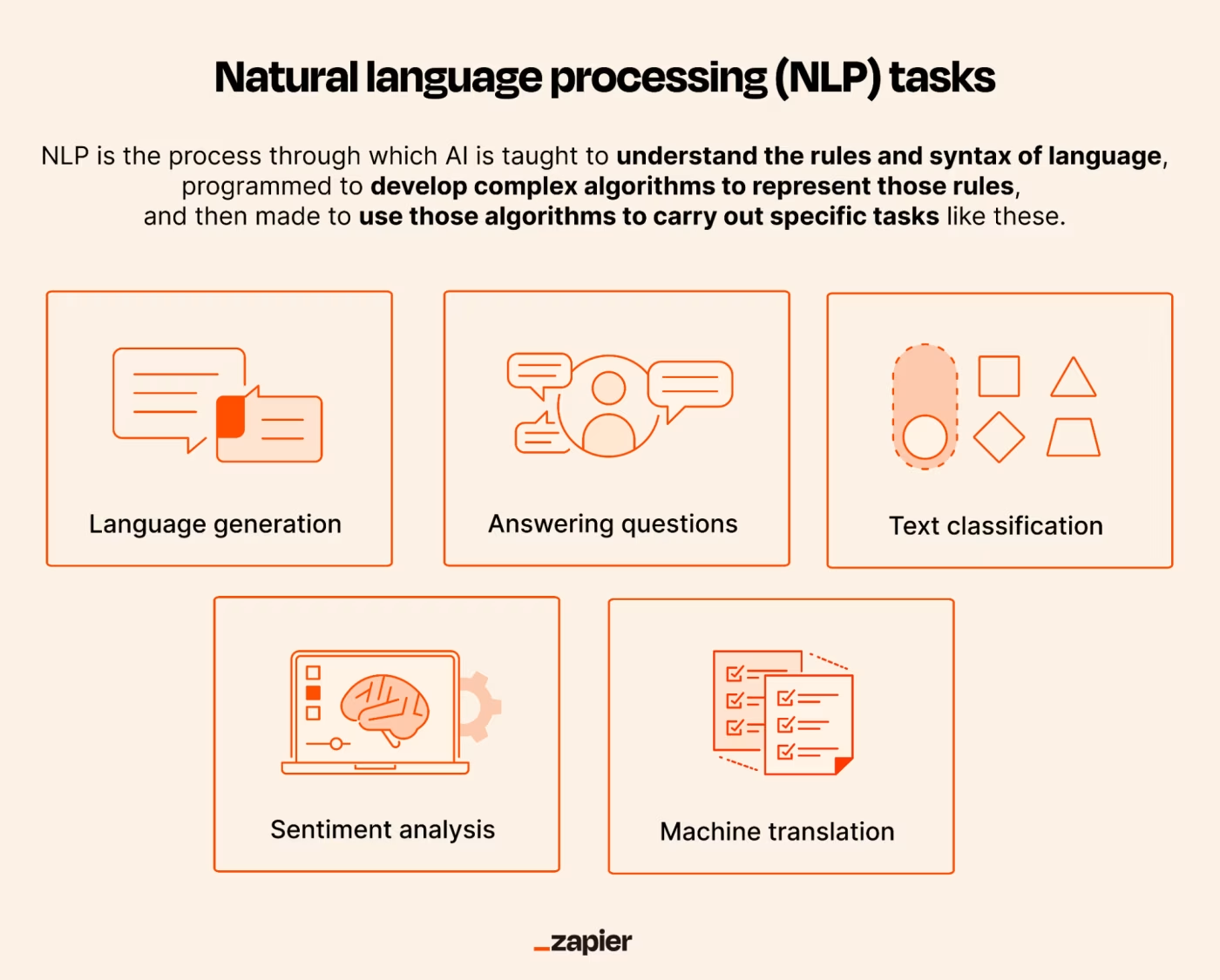

Natural language processing

Generating text is just one small part of what AIs can do with words. Natural language processing (NLP) is how AIs are able to understand, classify, analyze, reply to, and even translate regular human communication.

For example, if you’re asking someone to turn the lights on in a room, there are dozens of ways you could frame or phrase it. With a simple understanding of language, a computer can respond to specific keywords. (For example, “Alexa, lights on.”) But NLP is what allows an AI to parse the more complex formulations that people use as part of natural communication.

NLP is an important part of how GPT and other large language models are able to understand and reply to prompts, but it can also be used for sentiment analysis, text classification, machine translation, automatic filtering, and other AI language tasks.

Computer vision

Computer vision is the process by which AIs see and interpret the physical world, either through images and videos, or directly through their sensors.

Computer vision is obviously a key part of creating self-driving cars, but it also has more immediate uses. AIs, for example, can be trained to differentiate between common skin conditions, detect weapons, or simply add descriptive text, so people using screen readers have a better online experience.

Robotic process automation

Robotic Process Automation (RPA) is an optimization method that uses AI, machine learning, or virtual bots to execute basic tasks that humans would otherwise handle. For example, a chatbot can be programmed to answer common queries and direct customers to contact the correct support person, or automatically email suppliers an up-to-date invoice at the end of each month.

While RPA can tread the line between regular automation and artificial intelligence, intelligent automation (IA) takes it firmly into AI territory. It involves creating workflows that don’t just function automatically, but can also think, learn, and improve without human intervention. For example, IA can run an A/B test on your website and automatically update the copy with the best performing version—and then run another A/B test with a newly AI-generated version.

Machine learning vs. AI: What’s the difference?

AI and machine learning are two terms that are thrown around a lot together. While they’re interrelated, there are a couple of major distinctions. One way to think about artificial intelligence vs. machine learning: machine learning is part of AI.

AI is the umbrella term that encompasses any kind of thinking or reasoning done by a machine (that’s what makes it so hard to accurately draw boundaries about what is and isn’t AI). One of the things it definitely includes, however, is machine learning, which is where computer programs can “extract knowledge from data and learn from it autonomously.”

Many current applications of AI are either purely based on machine learning, or rely heavily on it during the training phase. At its recent WWDC conference, for example, Apple studiously avoided describing any of the new features it was announcing as artificial intelligence, instead billing them as machine learning. It’s less ambiguous and more technically accurate, although it doesn’t have the same sci-fi pizzazz.

In addition to machine learning, AI also includes a number of other subfields, including natural language programming, robotics, computer vision, and neural networks. More on that in a bit.

AGI vs. AI: What’s the difference?

When people talk about AI, they’re usually talking about narrow AI or weak AI (unless they’ve been watching too much MCU). Here’s the difference between narrow AI and the more lofty goal of artificial general intelligence (AGI).

What is narrow AI?

Artificial narrow intelligence (ANI) has been trained to perform a specific task, which it can do very well, but it isn’t generally intelligent.

Take ChatGPT. Most people can agree that it fits somewhere under most definitions of AI. And while it’s incredibly impressive, it’s also very limited. You can have fascinating conversations with it but only about stuff it understands from the data it was trained on.

You couldn’t stick ChatGPT into an autonomous car and give it directions to your destination. (By the same token, you can’t ask a self-driving car to write poetry).

What is AGI?

An artificial general intelligence (AGI)—also called strong AI—is the end goal of AI research.

AGI is the concept of a truly intelligent computer (or robot) that can reason, communicate, learn, and act in a human-like manner. Instead of being limited to one subset of tasks, it would be adaptable and capable of performing a wide variety of them. (Though, as with all things AI, no one definition is universally accepted or agreed upon.)

Put differently, an AGI would be able to both chat about the literary merit of Ted Chiang and drive you to your house.

My favorite “test” for whether something is an AGI or not was proposed by Steve Wozniak, the co-founder of Apple. In the Coffee Test, “a machine is required to enter an average American home and figure out how to make coffee: find the coffee machine, find the coffee, add water, find a mug, and brew the coffee by pushing the proper buttons.”

It’s silly, but it nicely encapsulates the level of flexibility a true AGI would likely need. And as you can imagine, we’re still a long way from that.

Applications of AI: What can AI do?

AI has now reached the point where it’s generally useful to people working in a wide variety of fields. Here are a few of the ways you—a regular human, reading this article written by a regular human—can use AI.

AI use by role

Some roles, like the ones below, are particularly ripe for AI.

-

AI in customer service—answering common questions, directing customers to the correct resources, performing surveys, and helping with localization.

-

AI in marketing—generating content, optimizing ads, translating campaigns into other languages, and performing additional analysis.

-

AI in IT ops—collecting data, speeding up resolutions, automating common tasks, and otherwise streamlining providing IT services.

-

AI in cybersecurity—detecting data breaches, hacks, and other computer security risks before they become a big problem.

Examples of using AI at work

Want to get even more in the weeds? Here are some super-specific ways you can use AI in your job:

-

AI at Zapier: How we use artificial intelligence to streamline work

-

How to automatically respond to Facebook Messenger with Zapier and OpenAI

-

6 examples of real businesses using DALL·E for visual content

Get more tips like this by looking at all of Zapier’s articles about artificial intelligence.

AI software

AI is already being built into almost every app, but here are a few categories where you have lots of options:

Once you start using AI tools, you can connect them to all the other tools you use at work using Zapier.

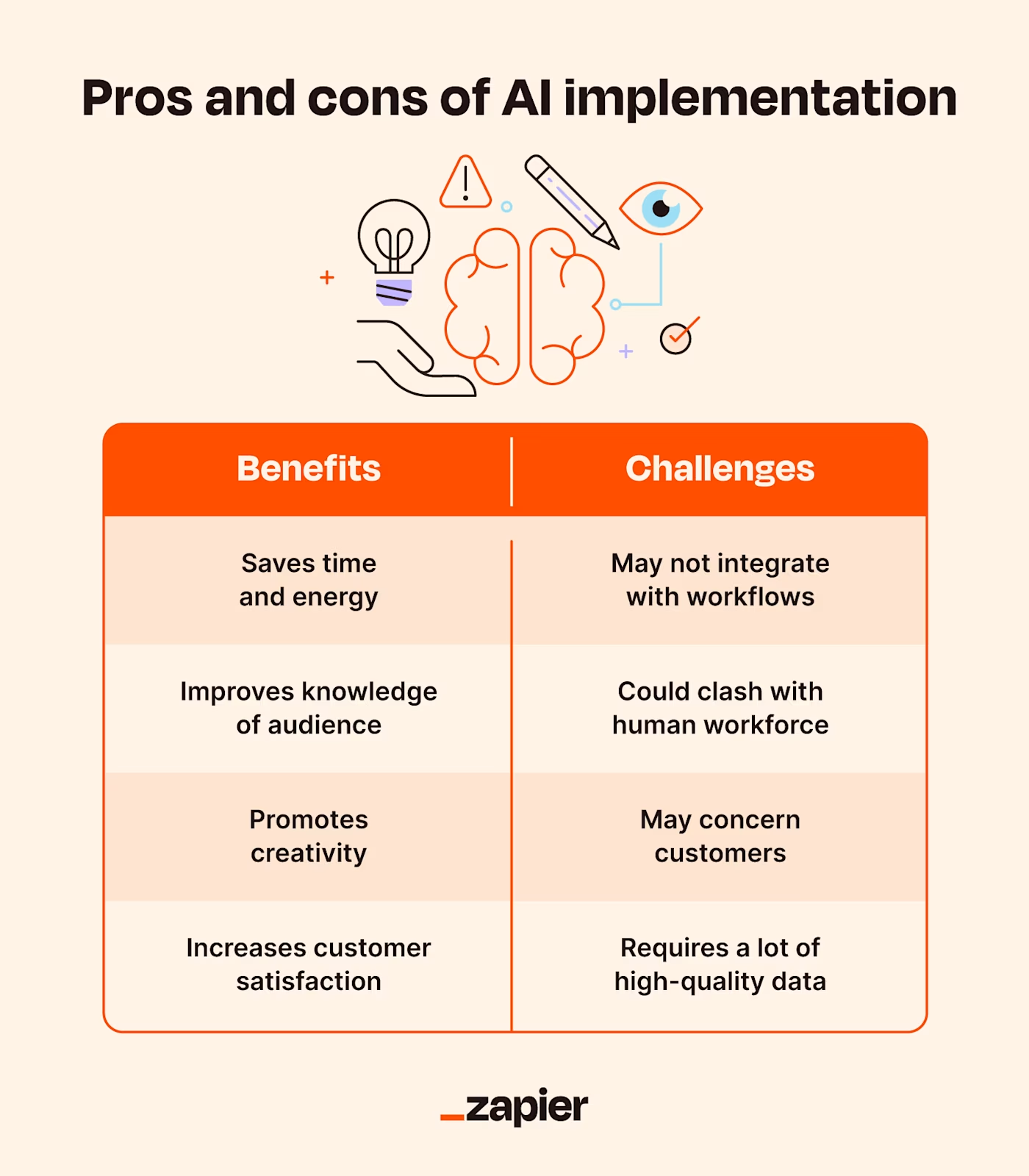

The pros and cons of using AI

People are scared of AI—and it makes sense. There are a lot of legitimate concerns around it.

Cons of AI

First of all, there are the ethical concerns: bias, misinformation, copyright infringement, the list goes on. But there are other reasons AI can be tough to use:

-

It’s still in the early phases, so it might not integrate perfectly with all of your existing workflows.

-

Not everyone is ready to embrace AI, so it can be hard to get humans to adopt it. Similarly, customers might be concerned if they see you’re using AI because they also may not be convinced yet of its utility.

-

It requires a lot of high-quality data. You can use pre-built generative AI tools to help you with your day-to-day, but if you want AI to have a deep impact on your work, you’ll need a lot of data for it to learn from.

Pros of AI

That’s the bad news. The good news is that AI has loads of benefits.

-

It saves time and energy, so you can focus on the work that requires a human brain.

-

It can increase customer satisfaction because you’re launching more features, creating more content, and speeding up your response time.

-

It promotes creativity by freeing you up to focus on more creative tasks.

-

It allows us to do things we never could have imagined (think: driverless cars, personal AI assistants).

The history of AI: How did we get here?

1940s

The first computers were built in the 1940s. While a lot of the ideas had been around for longer, the demands of World War II forced a huge amount of technological advancement and research spending. Devices to perform specific calculations—like the abacus—had been around for millennia, but these early room-sized computers were the first truly general purpose computing devices.

From early on, academics speculated about the possibility of mimicking the human brain using a machine. Neural networks—one of the models used in current AIs—were first hypothesized in the 1940s.

1950s and ’60s

Alan Turing published his famous Turing Test—that a computer that could have a text conversation with a human could be described as “thinking”—in 1950. But the term “artificial intelligence” itself wasn’t coined until 1956 at a conference at Dartmouth.

Since then, AI has been on a rollercoaster path to its current moment. The 1950s and ’60s were a time of great optimism. Around that time, political scientist H. A. Simon famously wrote that “Machines will be capable, within twenty years, of doing any work a man can do.”

1970s

That didn’t quite pan out, and the slow progress, technical difficulties, and other setbacks led to what’s called The First AI Winter. Research interest and government funding dried up, while certain problems remained intractable because computers just weren’t powerful enough.

Early 1980s

AI experienced another boom in the 1980s, this time largely driven by commercial interest. Some early “expert systems” (simple AIs capable of making decisions based on data inputs) were actually useful, and when used correctly, could save a company money.

Late 1980s to early 1990s

However, as with many much hyped new technologies, a bubble formed and then burst. The period from 1987 to 1993 is now known as The Second AI Winter.

Late 1990s – present

Since then, AI has been on the up and up. Deep Blue beating Garry Kasparov at chess in 1997 and IBM’s Watson beating Brad Rutter and Ken Jennings at Jeopardy! in 2011 are two of the most important cultural milestones, but the gradual behind-the-scenes research and development are more important.

Computers are now fast and powerful enough to handle the huge quantities of data to make things like neural networks, natural language processing, and computer vision work. It’s not that early researchers couldn’t imagine something like ChatGPT—it’s that they didn’t have the tools to build it.

AI has also slowly and imperceptibly been integrated into many of the products we use on a daily basis. Take Google. Over the past two decades, how it decides what sites to feature, what ads to serve, and what counts as a spam email has advanced to the point that it can only really be called artificial intelligence. It developed the transformer architecture that underpins GPT and other large language models in 2017, but it took five years for it to really come to fruition.

The future of AI

It might feel like everyone is suddenly talking about AI—and generative AIs in particular have finally reached the point where they’re useful—but really, the current moment has been building for decades. We’ve now reached the place where the theories and the computer hardware can work together to do some amazing things.

Here are a few predictions of where things are headed.

-

We’re likely going to see humans shifting to more strategic and relationship-building roles, while AI automates the rest.

-

We’ll probably start to see a lot more of AI interacting with AI, removing humans from some processes entirely.

-

We’ll see more job roles open up that focus on AI.

-

We’ll continue to see new AI apps crop up every day, but AI will also begin to be part and parcel of all the apps we already know and love.

One thing’s for sure: AI is going to change the way we work, and we need to adapt.

Related reading:

This article was originally published in June 2023. The most recent update was in July 2023.